Bottom Line Up Front: Training in specific heart rate zones is key to maximum cardiovascular training benefits. Here’s how to apply it and why.

The Most Important Variable

You may be performing standard “cardio” training by doing long slow bouts or repeated short high intensity bursts (those are better!) using time or distance as your guides. For example, performing a three-mile run (distance) or rowing for 30 seconds, then resting for 30 seconds (time). However, there is one important dimension of this that is often overlooked: heart rate.

When performing cardiovascular endurance training, your goal is to improve oxygen delivery to your muscles and improving the capacity/efficiency of your heart. Using distance or time to guide training is better than nothing, but it ignores the most important variable, heart rate.

Getting Started

First, to use heart rate data during training, you need a heart rate monitor. I recommend the Polar H10. It pairs via Bluetooth and can be easily read on your phone. You can display it in real time on your phone screen to watch it during training or wear it without having your phone nearby (it’s nice to leave it at home) and download the data into the phone for review later. This is a huge factor for those who can’t/don’t want to bring their phone with them but need to know the heart rate data.

Second, you need to have some idea about your heart rate zones. In order to estimate your max heart rate, a quick and dirty method is to take 220-age. For a 40-year-old, it would be 220 – 40 = 180 beats per minute (BPM). Now you can do some basic math to determine your zones, which we will do in increments of 10%. 90% = 162, 80% = 144, 70% = 126, 60% = 108. Please note that 220-age isn’t the best way. 206.9 – (0.67 X Age) is supposedly more accurate, but it yields pretty close results to the much easier 220-age. And since both are just estimates (to do it right you’d need to be tested by a professional in a lab), I am good with 220-age.

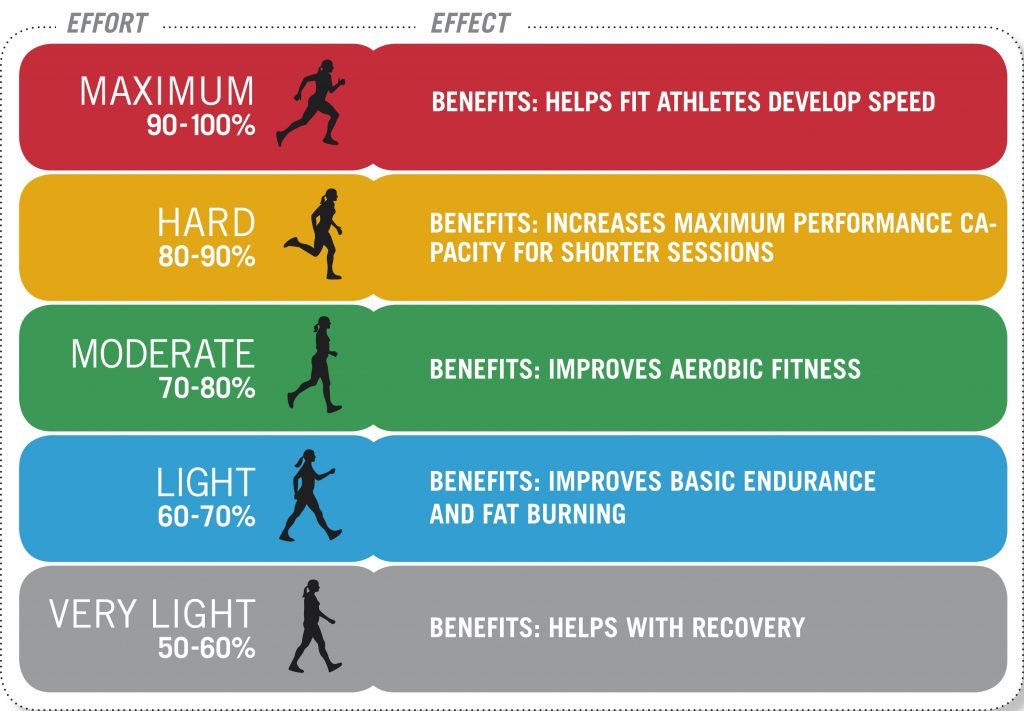

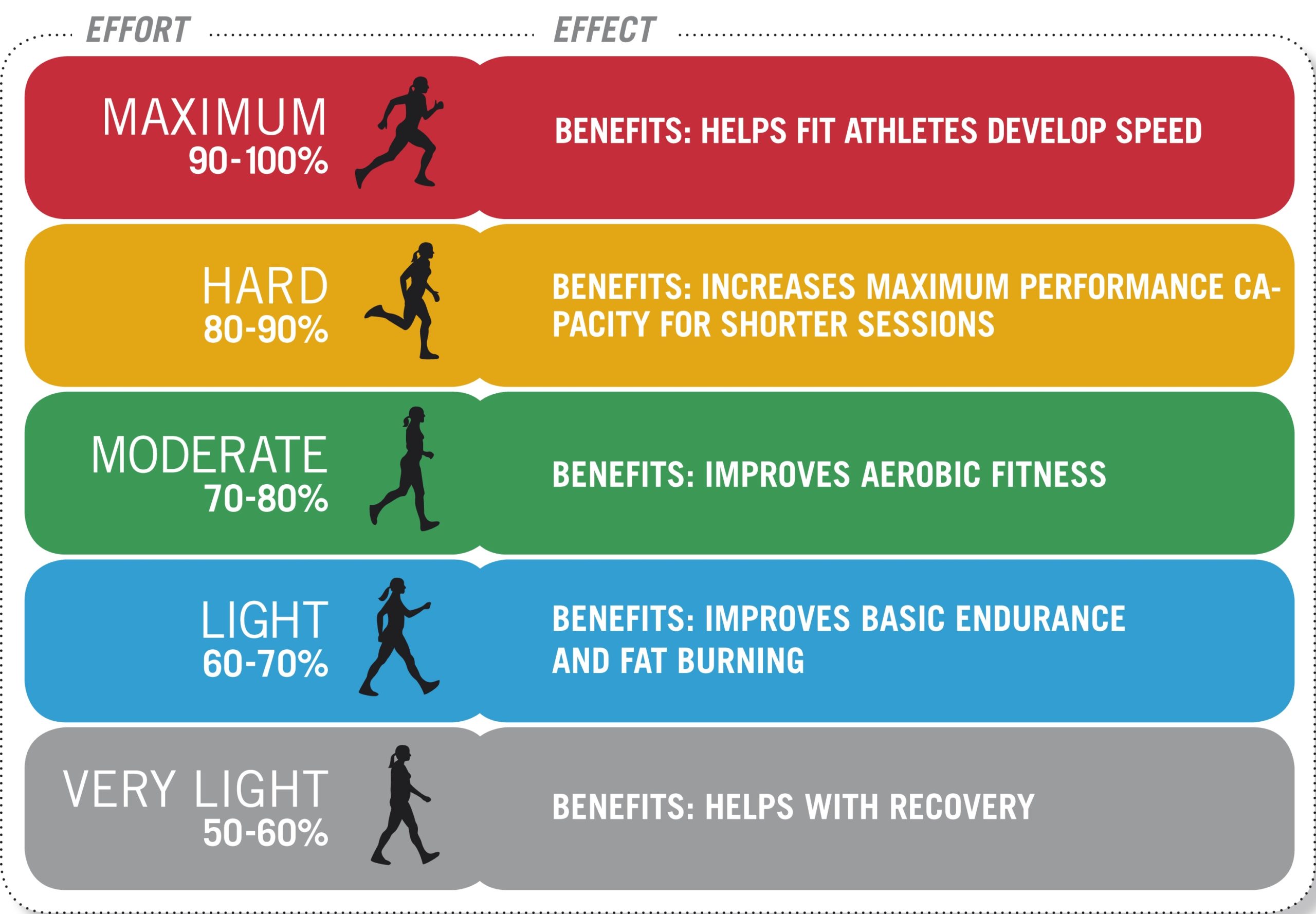

You can refer to the chart above for the differences between the effects of training in different zones.

Training Methods

Third, now that we have our heart rate zones based on our age, we can apply them to training. Here are some ways to apply them:

Use your heart rate to determine the upper end of your intervals. Say I am doing row sprints in my garage and I want to get not higher than 90% then rest, I would simply row until I got to 90% of my theoretical max heart rate and then rest. This keeps my heart rate below a certain threshold. Some people do this as a safety measure to ensure they don’t go too hard. Some experts recommend never going above 80% for maximum health benefits. For athletes, generally we are less concerned with the high end.

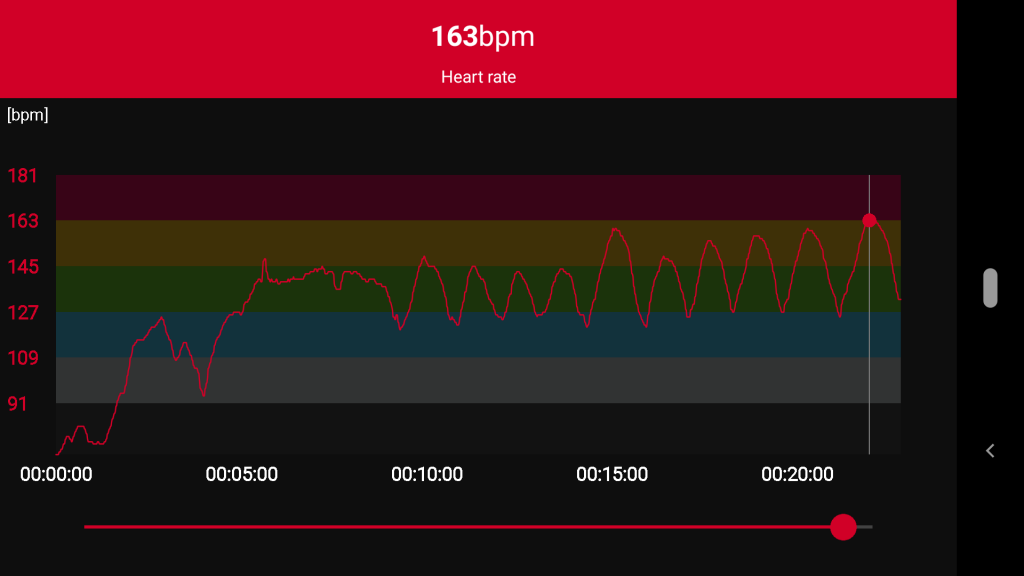

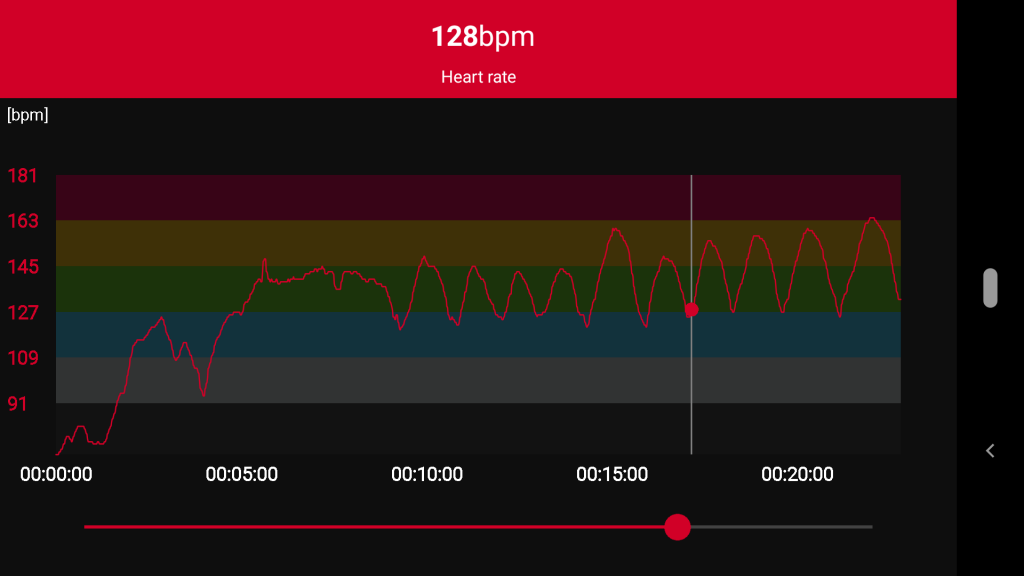

Use your heart rate to determine the lower end of your intervals. Now apply it the other way and combine it with time. I will row for one minute, then rest until my heart rate gets to 70% of my max, then row for another minute. This way keeps the floor at a minimum. I did it this morning in fact. I did repeated jump rope intervals and rested only until my heart rate got to 130 BPM (on/around 70%) then got back after it. Below is the resulting data from the Polar app.

Use heart rate to determine high and low end of your intervals. Probably the best method as it’s the most precise. Row until you get to 90%, then rest until you get to 70%, then do it again. Repeat per your desired effects.

Use heart rate to determine your pace when performing long sessions. Say you are performing a 10k row or a 5k run and you want to ensure you don’t go out to fast too early and fade. You can use heart rate to help you identify the zone to stay in. You may want to stay in the 70-80% range (mid-level of difficulty), so you speed up if you get below 70% max HR or slow down if you get over 80%. More advanced application of this is lactate threshold training, but if you are the kind of athlete who would care about this, you should already know what it is so I am not going to discuss it here.

Use your heart rate to determine intensity. Put on your Polar H10 and go for a hard run. Come home and analyze the data. How high did your heart rate get? How long did it stay in which zones? You may have thought it was exhausting yet your heart rate never got above 85%. Conversely, you may have thought you were running pretty moderately yet you were above 90% for a long time. Without the heart rate data, you really don’t know how hard your heart thought the session was.

Use heart rate to compare methods of training. Compare a 20-minute steady state run and 20 minutes of sprint intervals. You may find out, for example, your steady state run was at a 144 BPM average but your sprint intervals were actually 150 BPM. Or compare the effects of a one-to-one (30 sec sprint, 30 sec walk) versus a two-to-one (60-sec sprint, 30 sec walk) work-to-rest ratio.

Fat Burning Zone?

I will comment on it only because someone may be thinking about it: fat burning zones. You can see from the graphic at the top of the post, 60% is the “fat burning zone”. Roughly without a lot of science, your body utilizes fat (and not carbohydrates) for lower intensity activities such as light cardio but also for such things are standing at your desk typing or sitting in your car driving somewhere – essentially all day. Fat cells produce much more energy (ATP) per gram than glycogen (carbohydrates) so the body uses fat whenever it can. It saves glycogen for higher intensity situations. So doing anything at low intensity will use fat. Above 60-70%, it starts to get intense enough the body starts to use some glycogen to power the activity. The closer you get to 100%, the less fat you are using. Same with glycogen; at low intensities you are using some, just very little.

So theoretically, yes, you will burn more fat doing 30 minutes of light jogging at 60% than you would doing high intensity sprint intervals. However, you will have less of an effect on improving cardiovascular endurance and will burn less energy overall. Most professionals would still tell you that higher intensity bouts are better for “fat loss” as they use more total energy.

By the way, the body’s use of fat versus glycogen is the point of lactate threshold training (see, I had to get into it…). Using glycogen for fuel produces lactate as a byproduct. Lactate is often used interchangeably with lactic acid, but they are technically different. The body can clear lactate and reuse it for energy as long as the intensity is low enough. At some level of intensity, the body isn’t able to remove all the lactate fast enough and it builds up. The lactate itself doesn’t cause the fatigue but it indicates you are working at a high enough level that you will start to fatigue. This is new information to some as when I was in school BACK IN THE DAY we learned lactate was causing the fatigue. However, it seems new(er) research indicates the lactate as correlative not causative of the fatigue itself. We can still use blood lactate levels to show our relative intensity of exercise. If you want to read/listen to more, check out Andy Galpin’s podcast on this topic.

Finding the highest intensity at which you can train before lactate builds up is the lactate threshold. Knowing it is at 155 BPM or a certain pace when running can let the athlete know where to keep their steady state intensity. If my lactate threshold pace is 7 mins/mile and I ran at 6:50 for the first 10 miles, I would finish at say 3 hours, 30 minutes whereas if had run at 7:05, I would have finished at 3 hours, 10 minutes because I got less fatigued (less lactate produced) despite running slower at the beginning.

Final word to the wise, lactate or lactic acid has ZERO to do with muscle soreness. It doesn’t stay around and need to be cleared out to alleviate soreness. It is a completely incorrect thing that everyone somehow knows. Stop spreading the myth! Google it if you want to read more.

Please post questions or comments below. Enjoy.

I dont like going outside but know i understand i have to be motivated

Sorry to hear that! Motivation is very important. Whatever you have to do to find it, I would make this a priority. Going outside’s very good for you obviously. Best of luck!